Artist Adjo Kisser speaks to CKR Researcher, Amogelang Maledu about collective art practices

Adjo Kisser (b. 1992) is an artist whose interest in narratives, and the archival form has resulted in recent investigations into sound, collectivity and the cultural initiatives of liberation movements across the continent of Africa. However, Accra, as one of the city-studios where national infrastructure was used in the broadcasting of anti-colonial sentiments and ideas, becomes an important springboard in her research.

Until 2019, the narratives that formed the basis of her work were those garnered from eavesdropping on conversations in public places in Accra and Kumasi, Ghana. These narratives had inspired the humorous and satirical tone of her cartoonish drawings which featured blue-skinned characters with painfully frozen grins.

The Billboard Series, Loco Shed, Kumasi Railway (Adum). 2016. Photo credit: Derrick Owusu Bempah

Her drawings later took a more collaborative turn through The Billboard Series, instigating her interest in community-based artistic projects. She continues to interrogate what the changing notions of ‘community’ today can mean for the production and experience of art through an embrace of processes that encourages incidental discoveries and serendipitous moments.

It’s a Fluke. Trust me. Incomprehensible and nonsensical actions in Hamburg. 2019. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Kisser recently concluded a PhD in Painting and Sculpture at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi-Ghana, where she lectures and remains an active member of blaxTARLINES KUMASI – an experimental incubator for contemporary art that has featured on ArtReview’s list of Power 100 chronicling the most influential people in the contemporary artworld. She has exhibited in Ghana, Germany and Uganda, the most recent being Silent Invasions: The Art of Material Hacking.

Adjo Kisser public lecture at Michaelis School of Fine Art. 2024. Video courtesy of CKR.

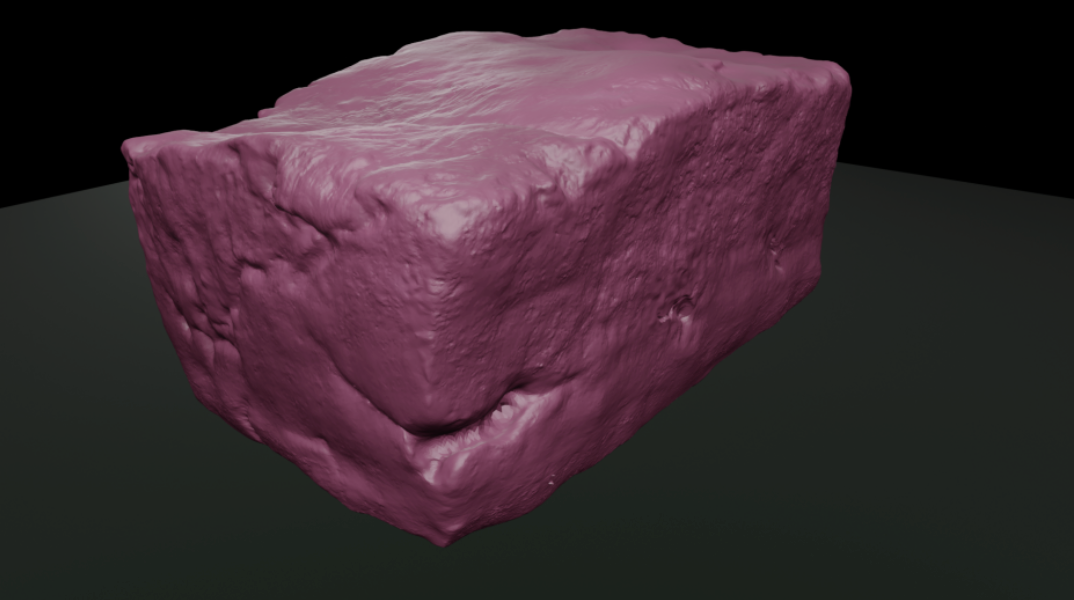

3D model of brick in Clay Bricks: Okukungaanya, 2023. Photo courtesy: Arthur Wamala Luganda.

She currently lives and works in Kumasi and Accra, Ghana. CKR’s Amogelang Maledu interviews her following her research trip to Cape Town as part of her Fellowship with the research centre based at the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Art History and Discourses of Art department.

Amogelang Maledu (AM): I want to start predictably, with your impressions of Cape Town especially as a first time visitor. But, perhaps I preface it like this: as someone who was inspired by eavesdropping in public places in Ghana – which in turn developed into methods of community-centric art making practices – are there any noteworthy conversations that you overheard or noticed during your stay in Cape Town that has informed any part of your art or research? If so, what have those been?

Adjo Kisser (AK): I was initially anxious about visiting Cape Town, likely due to the uncertainty of what to expect. It became clear to me later in my trip that this anxiety may have been the result of feeling overwhelmed. Without a doubt, there would have been many inconspicuous encounters that unknowingly shaped my outlook.

However, there were the seemingly mundane moments that stood out to me, from the few art exhibitions and artists’ studios I visited to the book launches, interventions at the Chimurenga Factory, and the regrettable late nights spent by myself as I endured a terrible fever. Beyond Cape Town’s breath-taking views, there was the startling encounters with its topography and the ways it was complicit in the organization of its occupants. I also recall fondly my cosmic encounters from visiting The Iziko Planetarium and Digital Dome in the Iziko South African Museum, South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO), and South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO). These were tremendously helpful towards imagining possible futures.

AM: Your work, The Billboard Series, incidentally took a collaborative turn, in many ways also positioning the sensibilities of your artistic practice within that of “the curatorial” and that of multiple authoring, where you are not only expanding notions of exhibition-making beyond the white cube, but simultaneously challenging the notion of “the singular genius artist”. How has this project shaped your interdisciplinary practice: both as an artist, academic, curator and art community organiser? Is it gleaning into process-led methods of making? Strategies of contingency and/or necessity or it is practices largely shaped by the context and its people?

AK: There are very real challenges with summarizing my work. Yet, the embrace of a non-totalizable form in this way is a deliberate one. My projects are meant to be encounters with life itself. Although, they may seem to adopt process-led methods of making, strategies of contingency and/or necessity, they cannot be limited to that. Thankfully, I have also never considered my role as artist, academic, curator and convener as separate. This has a lot to do with my training at the Kumasi school, where I am surrounded by a community that has always looked to push the boundaries of art. The Billboard Series was one of those projects that led me to ask very new questions about art and its place in community-organisation today. These inquiries have continued in projects like It’s a Fluke, Trust Me which took place in Hamburg-Germany as well as ongoing long-durational and genre-defying projects like Learning from an Onion; Working as DJ and Clay Brick: Okukungaanya. It is a never ending inquiry.

AM: You are currently doing your PhD in Painting and Sculpture at Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) where you also teach. Can you share with us about the pedagogical approaches developed from your university, particularly the Emancipatory Art Teaching Project that was developed in 2003 at KNUST? This is important for us as CKR given the context of the university we are based in – UCT – that was at the centre of rightful protest action under the #RhodesMustFall movement with amongst other calls, decolonial education. We are curious about how to learn from other African universities in how their pedagogies respond to particular sensibilities considering the colonial inheritance that comes with their foundations.

AK: Yes, I just concluded my PhD in Painting and Sculpture at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), where I also teach. Before the institution of blaxTARLINES KUMASI in 2015, there was the generative pedagogical project launched in 2003 by kąrî’kạchä seid’ou. This project was what he referred to as the Emancipatory Art Teaching Project, which I became a beneficiary of later. It began as a response to a failing curriculum which was really a regurgitation of a contrived and colonial model of art. In response to this curriculum, the Emancipatory Art Teaching Project promised intellectual emancipation by encouraging political indifference to any medium, form, style, genre, process, or trend of art, so that exhibiting artists could be trained as exhibition-makers, and as neither. This was a complete rethinking of the exhibition form, its conception, making and dissemination, which led to many guerilla interventions by students across the city of Kumasi, Ghana. It was this project that instigated the formation of the sharing community, blaxTARLINES, which is built on axioms like radical sacrifice and views of art as a non-reciprocal gift.

AM: Finally, you know that at CKR we are passionate about socially engaged art practices and interventionism in Africa and its diaspora. Your research practice was inspired by how city-studios in Accra became key national sites that broadcasted anticolonial sentiments during independence in Ghana in the 1960s. What role do you think art plays in the contemporary when networks of solidarity across geographies has become increasingly important for marginalised identities? Moreover, what role do nation states play at a time where their ideological imperatives are being challenged given how they contribute to various forms of oppression through nationalist agendas that have harmful ramifications?

AK: If there is anything I have tried to always keep in mind, it is that we cannot have predetermined values assigned to any set of correspondences today. What is considered progressive today can always be co-opted for not-so-progressive purposes. This is clear when we consider terms like ‘democracy,’ ‘participation,’ ‘nationalism’ and even ‘care,’ which have all become very popular today. Art is no different. It is not by itself immediately emancipatory. It can be useful in dismantling structures and creating new accesses, yet the reverse can also be true. What I believe should be the focus is inventing techniques, apparatuses, or technologies that neutralize structures that preserve the difference between those who possess a capacity and those who do not. This could mean finding our cures in the poison.