Water as Rhizomatic Impulse

Emmett Till rides the crest of the Pearl, whistling

24 years his ghost lay like the shade of a raped woman

and a white girl has grown older in costly honour

(what did she pay to never know its price?)

now the Pearl River speaks its muddy judgement

and I can withhold my pity and my bread – Audre Lorde, “Afterimages”

Lorde’s deployment of the associative power of memory offers new ways of thinking about how water confines, constitutes and sublimates the boundaries of blackness. Through the retelling, reimagining and the reconstitution of Emmett Till – a figure that haunts the black visual and literary imagination –and by situating Till in waters with which her own body is familiar, Lorde makes visceral the literal and figurative weight of water, what Elizabeth DeLoughrey (2010,703) refers to as “heavy with water- an oceanic stasis that signals the dissolution of wasted lives” - [1]. In his seminal text on the work of the imagination titled “Water and Dreams, An Essay on the Imagination of Water”, Gaston Bachelard (1982) writes that there are two sorts of imagination: a formal imagination (which can be defined as that which gives life the formal cause) and the material imagination (through which the material cause is born). For Bachelard, the two are not necessarily diametrically opposed; they are in inexplicable cooperation. It is difficult to define where one ends and the other begins. Yet ultimately, Bachelard informs us that what is at stake is the material. The formal imagination is an amalgamation of perishable form and vain images, but the images of the material are dreamt deeply and substantially. They take root in the heart. Perhaps Bachelard’s privileging of the material is a consequence of opposing it to form, that primal language of speaking art and aesthetics figured most concretely in our minds by Charles Baudelaire and Clive Bell. Yet there are other speakers with whom the material is in conversation. The most pertinent to our cause is that of the surreal. In his Manifesto for Surrealism, Andre Breton (1924) states, “Surrealism rests on the belief in the highest reality of certain hitherto neglected forms of association; in the omnipotence of dreams; in the disinterested play of thought” (10). Surrealism turns us away from the materialist or “physical mechanism” and then “substitute(s) itself for them in the solution of life’s principle problems” (10).Breton argues that surrealism does more than unsettle literary and aesthetic standards; rather, it evokes meditation and wonderment of the veiled – and at times ineffable – regions of imperceptible reality (8). The surrealist imagination seeks to excavate, and possibly unveil, the “unspeakable reality” which is “concealed behind this forest of symbols” (8). In order to do this, the surrealist writer or artist must “attempt to express the inexpressible…through the alchemy of language in order to reach” the dreamscape, or the ‘dynamic reality’” (10). Therefore, the grounding motivation of surrealism lies in its “impossible quest of (the) infinite expansion (or deconstruction) of reality” (12).

In her essay, “1943: Surrealism and Us”, Suzanne Cesaire (2009) argues that surreality, as an ethic of creative-being-in-the-world, “lifts the spell of the impassable barrier between the inner world and the outer world” (34). The surreal, for her, is not merely an ontological demarcation in the same way that an ‘inner world’ and an ‘outer world’ are. The surreal is more fundamentally an ethic, “a unique faculty” that “endlessly sustains a massive army of negations” (37). In the zone of the surreal, the barrier between the inner world of perception and the external world of events hangs on the gulf of negation. The refusal of the barrier enables a convergence of the dreamscape and the real-as-it-is-experienced, where these two points of existence become conceptually inseparable, or may even become conceptually null.

We can observe from the various waves of the black aesthetic tradition – particularly the allegorical or imaginary strain of this tradition – that there are at least two faces of water. One face of the water is what Mapule Mohulatsi (2019) has described as the “materiality of the ocean” and other bodies/embodiments of water (Mohulatsi 2019, 04) this face of water contains, or is, an “archive of waste” (7) or what Derek Walcott (2007) referred to as the grey vault of memory and history. This archival or mnemonic façade of the water “reflects temporal depth and death, in fact, the water is the element which remembers the dead” (DeLoughrey, 2010, 704). Mohulatsi conceptualises the archival depths of the material waters as a “rubbish dump” (2019, 06). Thus, she rejects “an ordered textual archive for a heavy rubbish dump that can produce almost anything” (9).This rubbish dump is unveiled/unlocked within “the ocean’s underworld, not as a separate entity, but rather, as a network that is connected to our localization, not only as gulping and swallowing, but also as keeping and spurting, vomiting and chewing” (11). To look at water in this way requires an art of reading the material textures of water “that refuses any symbolic association with a straightforward, observable telos… or else the soothing music of a premodern idyll, and instead forces us to confront the legacies of brutality… that mark such spaces” (Bennett, Paris Review, 2018). Since this blackened reading of the water refuses telos, we can infer that even if it may be the case that the water is read as a “materiality”, it is not read strictly through the materialist imagination. This method of reading water warrants an intersection of a materialist orientation of reading the reality of water and an allegorical orientation of conceptualising the ‘face’ of water. So, on one hand of the hermeneutic scale, it contends with the reality or substance of material water and, on the other hand, it contends with the symbolic elements that emanate from the tumultuous, terrifying and, as Mohulatsi puts it, “demonic” history of water (Mohulatsi, 10).

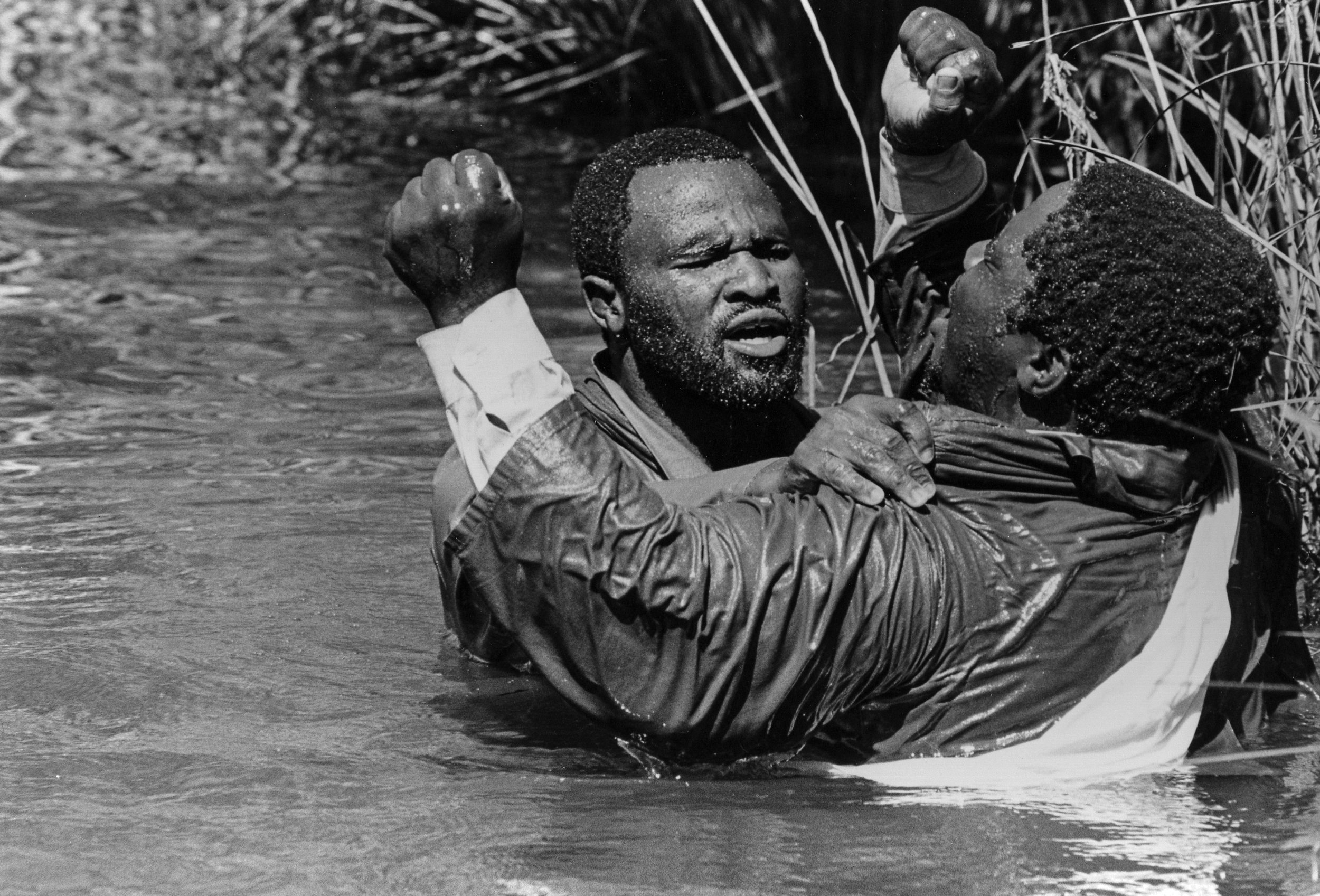

Immersion baptism at Orlando, Soweto of the Zionist Church from Meadowlands Zone 4, 1991, Courtesy: Ruth Motau / Photo Legacy Project (PLP)

Lorde’s poetics conjure this material-surrealist dialectic. She articulates how water permeates and co-constitutes the metaphysical and ontological body of blackness. By renaming the Tallahatchie (the river where Emmett Till’s body was drowned) as the Pearl river, the main body from which the Tallahatchie tributary flows, Lorde – inadvertently or by design – brings to the fore the rhizomatic qualities of water, what Suzanne Cesaire is referring to when she speaks of “the river of grass snakes that I call my veins”.

In the geographic imaginary, water functions as a networked system that demarcates the boundaries of a drainage area. To the untrained eye – those of us who hold water without the language of geomorphology – we perceive the complex systems of tributaries, streams, the dead pools of swamp, the lingering sensuality of the marsh, wetland and the floodplains as a labyrinth whose materiality mirrors the contours of black life and death. At a deeper level, what Lorde is alluding to is the redundancy of naming water, that is, isolating through language supposedly different bodies of water, for we see that water operates as a mnemonic device that allows us to retrieve the “afterimages'' of seemingly disparate events and, in so doing, articulates the ecological devastation racial capitalism has wrought on black life.

In “The Black Aquatic”, Rinaldo Walcott (2021) describes the “black aquatic as the fact of black people’s lived relation in and to bodies of water as both self-constitutively historical and contemporary” (65).For Walcott, the black aquatic is an attempt to pursue the relationship black people have to bodies of water and to provide an aesthetic narratology and hauntology of contemporary black subjectivity. Walcott, however, does his own project a disservice by limiting the fluid and fluvial potentiality of water within the discursive boundaries of ‘bodies .His use of ‘bodies’ presents water as occurring in discrete geographic entities, isolated linguistic phenomena which blackness might approach in order to access different parts of its own ontological corpus. Mohulatsi, however, has made glaring that the black aquatic is similarly an amalgam of institutional and infrastructural logics that regulate water flows. It is the deadening weight of water that wastes black life The slums, the ghettos, the grottoes and the rural areas – those sites conceived of as modernity’s periphery –– are where the black aquatic finds expansive opportunity for rhizomatic expression.

It is a project that encourages us to think about water through saturation. Melody Jue and Rafico Ruiz (2021) present a saturation as a “heuristic material” (2); that is, an interpretive lens that may guide how scholars speak about particular phenomena, based on some material or environmental feature. In the arts of black allegory, water has often been imagined as the site and the host of the sacred (Zauditu-Selassie, 2009). Water is either imagined as a purifying force, or as a passage to the true home of the dejected or liminal subject. Within these imaginings, drowning always lingers in the shadow of water’s material and cosmological life. Drowning announces water’s destructive force in a manner that evokes Lorde’s negation of specificity. All waters innately possess the ability to truncate breath and, in so doing, bring death to the shores of one’s existence. Drowning embodies water’s spectral and surrealist potentiality. It holds it well. It disassembles the boundaries that differentiate the various liquid entities, such that there is only water, pooling disastrously in the hole around which black life oscillates. “Sea receives a body as if that body has come to rest in a cushion, one that gives way to the body’s weight and folds round it like an envelope” writes British-Guyanese author Fred D’Aguiar in Feeding the Ghosts (61). In the Middle Passage, drowning carries the promise of escape from the hold of the ship, even if it means slipping into the abject forever of the saline water. D’Aguiar’s sea demonstrates water’s tempestuous manner, its ability to hold both death and freedom in its wake, to suspend the black body infinitely in the liminal space of unfreedom. Drowning has a deathly reverence that treads the line between materiality and cosmology. It tethers sea to river to sewer system; it acts as a chord that ties the waters that loom large in the body of the black radical tradition those that occur as footnotes, those that forebode the mundanity of the everyday life of neoliberalism. Drowning is water’s suppression of breath, its engulfment of the lungs and the dissolution of the barrier between within and without. The human body is constituted of sixty percent of water; the body emerges from the liquid world of the uterus. Perhaps drowning is a perverse gesture towards equilibrium. We see through Marcus Rediker’s (2014) notes on the conditions of the slave ship, an entity that suspended the black at sea, that drowning also offered a reprieve from the hold of the ship and the gratuitous violence the slave was subjected to onboard. Rediker’s sentiments on the slave in the fleeing the hold of the ship read thus:

Some jumped in the hope of escape while docked in an African port, while others chose drowning over starvation as a means to terminate the life of the body meant to slave away on New World Plantations… One of the most illuminating aspects of these suicidal escapes was the joy expressed by the people once they had gotten into the water. Seaman Isaac Wilson recalled a captive who jumped into the sea and “went down as if exalting that he got away. (125)

As a “heuristic material”, to use Jue and Ruiz’s term yet again, drowning holds the unholy trinity of past, present and future in its grasp. It is, as Joshua Bennett (2018) reminds us in his gesture towards a black Hydropoetics, that Western cosmologies and spiritual practices informed the belief in water’s redemptive capacity and, as a belief, it this ethic that allowed the captive to view biological death not as an absolute conclusion but a way to return to their native land (108).

Ruth Motau’s photographic treatise on blackness bears the cosmological weight articulated by Joshua Bennett. These works – which are often confined to the genre of documentary photography, owing to Motau’s many years as a photographer for the newspaper the Mail and Guardian – should rightly be viewed as surrealist allegories that attempt to make salient the mythic, symbolic and ritual power of water. In this powerful evocation of the surrealist impulse and its tendency to pervade the quotidian, a priest is seen submerging a young congregant of the African Zionist Church. The camera captures the congregant in that moment where they perceive drowning as imminent; their submergence into the water represents an invitation to the great beyond. Motau perceptively renders the banality of black life as the site where the surreal and material converge. As the two figures in the photographs struggle against each other and the ceaseless force of the stream, these images draw our attention to the manifold historical, aesthetic and material modalities through which water constitutes – and more importantly immerses – black life. Drowning, here, is a genre of immersion. The BaKongo cosmogram, for example, signifies the symbolic and philosophical depth of immersion in African cosmology. It centres the ontological field of water as the sphere from which one’s relation to mnemonic time is mitigated. Water here facilitates the double bind presented by Suzanne Cesaire’s (1945) surrealist vision; it allows the subject to overcome their nostalgia for earthly space (45) whilst allowing for a return to oneself (37). The subject’s personal universe is centred on the aquatic “plane of immanence” (Deleuze and Guattari 2004,266 . Their immersion into water and emersion from water traces a mnemonic dimensionality, a kind of memorial reality. When one emerges, they must remember from water the paradigms of life. When one is immersed, they must remember in water the paradigms of death.

Black life is heavy with the weight of water’s material and surrealist capacity. It is a force that contours black aesthetic traditions. It reminds us what is at stake. At the time of writing this, the residents of Soweto had been without water for three days owing to the ongoing search for Khayalethu Magadla, a six-year old child who fell into an uncovered manhole while playing in a Dlamini park with his friends. As Emmett Till’s body rode the crest of the Pearl drowned by the gratuitous violence of an anti-black antebellum doctrine, so does the body of the black child ride the waves of a subterranean tide of everyday liquid and infrastructural violence that contours the black quotidian.

[1] In “Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity,” Associate Professor of English at the University of English, Elizabeth DeLoughrey offers new modalities of reading oceans and their haunting of literary imaginaries. DeLoughrey suggests that “heavy” water is a sign of an oceanic stasis that signals the dissolution of wasted lives. This heaviness is apparent in Lorde’s poesis, wherein the waters of the Pearl are trusted to dissolve Emmett Till's wasted life.

Bibliography

Bachelard, G. (1982). Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. The Pegasus Foundation.

Bennett, J. (2018). "Beyond the Vomiting Dark": Toward a Black Hydropoetics. In A. H. Osborne (ed.), Ecopoetics: Essays in the Field (pp. 102-120). University of Iowa Press.

Bennett, J. (2018). “Revising “the Waste Land”: Black Antipastoral and the End of the World. The Paris Review.https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/01/08/revising-wasteland-black-antipastoral-end-world

Breton, A. (1924).The First Manifesto of Surrealism. In Harrison and Wood (eds.), Art in Theory 1900-1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, (pp.87-88).Blackwell Publishers.

Cesaire, S. (2012). “1943: Surrealism and Us”. In Maximin Daniel (ed.), The Great Camouflage Writings of Dissent (1941-1945), (pp. 34-38). Wesleyan University Press.

D’Aguiar, F. (1997). Feeding the Ghosts. The Ecco Press.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2004). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. University of Minnesota Press.

DeLoughrey, E. (2010). Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity. Theories and Methodologies 125(3), 703-711.

Gilroy, P. (2017). "Where Every Breeze Speaks of Courage and Liberty": Offshore Humanism and Marine Xenology or, Racism and the Problem of Critique at Sea Level. Antipode 50(1), 1-20.

Jue, M. & Ruiz, R. (eds.) (2021). Saturation: An Elemental Politics. Duke University Press.

Lorde, A. (2000) The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde .W.W. Newton Company.

Mohulatsi, M. (2018). Black Aesthetics and the Deep Ocean [Master’s Thesis]. Wits University.

Rediker, M. (2014). Outlaws of the Atlantic: Sailors, Pirates, and Motley Crews in the Age of Sail. Beacon Press.

Walcott, D. (1992). Collected Poems (1948-1984). Faber and Faber.

Walcott, R. (2021). The Black Aquatic. Liquid Blackness: Journal of Aesthetics and Black Studies 6(1) , 62-73.

Zauditu-Selassie, K. (2009) African Spiritual Traditions in the Novels of Toni Morrison. University of Florida Press.